Student’s passion for the environment leads to a smarter way to clean up oil spills

High-school senior Naomi Park knows that climate change is a problem affecting the entire world right now. So, for this year’s Stockholm Junior Water Prize competition, she set out to find a way to help solve it. With a sponge.

The world’s oceans have to deal with a lot: plastic waste, oil spills and increasing levels of carbon dioxide. Oceans absorb nearly one-third of airborne CO2 emissions, and they contain more than 170 trillion plastic particles. Every year, 1.3 million gallons (nearly 5 million liters) of crude oil are spilled into oceans.

Naomi Park wanted to find a solution that could help address all these problems at once, and she did it through her Multi-Functional Remediation Framework. It’s basically a sponge that, when lowered into seawater, can absorb up to 92% of benzene from oil spills and up to 95% of CO2. As an added benefit for the environment, the material used to make the sponge comes from plastic Styrofoam waste.

Park’s innovative solution won her the 2023 Stockholm Junior Water Prize, an international competition organized by the Stockholm International Water Institute. She also recently conducted original research at the Research Science Institute, a summer research program hosted by MIT for 100 outstanding high school students from around the world.

Making Waves spoke with Park about her invention, her interest in science, and why she believes young people need to get involved in environmental issues.

What got you interested in science, and what was your first invention?

I think it all started in the third grade. We had this program where every Friday we could miss one or two classes and do something called “genius hour,” where they let you roam free to invent something or delve into a topic that you're passionate about. I was really excited about it, so that first night I went home, and I was in my room, and I thought, I need to solve something.

I actually had a big problem with hand cramps at the time, from holding things too tightly, especially my pencil. So I created a tiny sensor that you could attach to any writing device, and it would emit a light based on the tightness of your grip.

My biggest takeaway from that was I had experienced a problem firsthand and was able to solve it. So that kind of innovation aspect and being able to create something was what led me to want to do research in high school.

Is solving problems still how you approach science?

I really like doing research, and for me it’s definitely about that initial motivation of seeing problems, even within your own community. I live in Greenwich, Connecticut, which is near the Long Island Sound. There’s a park there that many people are very fond of. But they recently told us that because of rising sea levels and climate change, in about 50 years, half the park could be covered by water.

When we think of climate change, we often think it's never going to happen to us. We can just leave that problem to future generations, but seeing that problem in my own small town was eye opening.

I’ve been doing a lot of environmental research since the ninth grade, but I'm also really interested in the policy side, focusing on how we can implement new technologies and reach out to politicians.

How do you see science and that kind of advocacy working together?

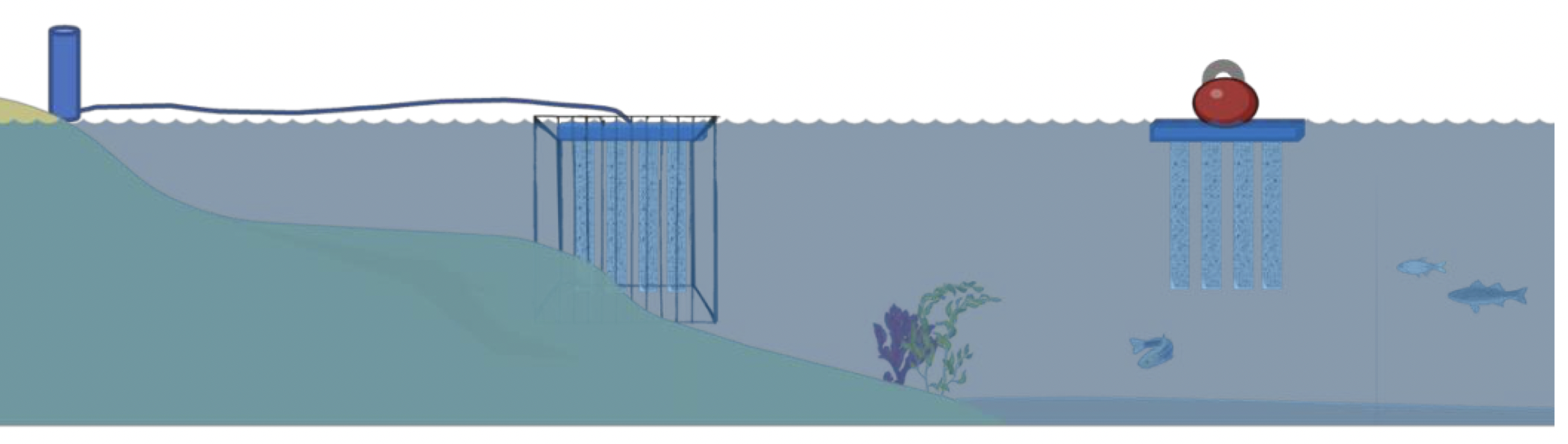

That’s actually something I wanted to address in my project. One of the pollutants I was addressing was oil spills, and generally when we think about oil spills, we think about the visible surface contamination, right? We always see those images of oil floating on the surface of the water, which is very harmful, and we have methods to solve that, such as oil booms.

However, there's a big problem that isn't being addressed, and that's this soluble oil that's being released and spreading underwater. So I was able to create a device to remediate that.

But when thinking about implementation, I realized that in the real world, it's not feasible to get rid of existing methods and processes overall, because that's just like not how the world works.

So one method of implementation that I envisioned was attaching my sponges to traditional oil booms. My invention could work in a symbiotic relationship with existing methods, which would hopefully work better for people who are more resistant to change.

Aside from oil spills, how could your solution help with removing CO2 from oceans?

That’s a question that’s come up, since the oceans are so huge, and I’ve thought a lot about it. In oceans there’s these things called acidification hotspots, where carbon dioxide dissolves in seawater and creates an acid. To remove CO2 from these areas, I would envision creating a floating barrier of sponges that could be placed there to protect coral reefs and marine life.

Why do you think it is important for young people to get involved in water issues and the environment?

Young people need to learn about these issues early on, so we can carry it into our adult lives and pass it on to our children.

It’s been really inspiring being at World Water Week and meeting other finalists in the Stockholm Junior Water Prize. I’ve been making friends with people who live thousands of miles away from me, but we’re all connected by the same interests.

Have you had a mentor or other people who have inspired you in your research?

Yes, my mentor at Greenwich High School, Andrew Bramante, has truly been such an inspiration to me. I've been working with him for three years, since the ninth grade. He runs the science research program at our school, and it’s really been life changing. He's stayed with us after school and worked with us on weekends and holiday breaks. He’s one of the most dedicated people I've ever met.

Also this summer when I was at the Research Science Institute through MIT, I worked under a professor, Dr. Haruko Murakami Wainwright, and it was really inspiring to see the environment she was able to create. She’s not only a professor, but she has students and runs her own lab. Before that, I always thought labs were about one person in charge and others following orders, but just seeing how collaborative she made everything, and how she gets to work on so many different projects that touch on so many different issues, was really inspiring to me.

Do you plan on continuing to do research on water and the environment?

Many of my projects in high school have been on water – it’s a subject I really love. I think I want to go into Civil Environmental Engineering and continue doing research. I want to go into academia, and maybe one day be a professor and have my own lab. Big dreams.